For the last 10 years, just one brewery has won the World Beer Cup (WBC) Gold Medal in the category “Belgian Style Sour Ale”. With 6 consecutive WBC Gold Medals, that brewery is Brouwerij Boon. And that accomplishment provides just one demonstration of the skill, quality, consistency and dedication that Frank Boon and his sons, Jos and Karel, bring to their craft.

Brouwerij Boon makes lambic beer. Lambic beers—whether straight lambic, faro, geuze (also spelled gueuze) or fruit based—are indigenous to Brussels and to the rural Zenne (or Senne) River Valley in Belgium. The beer is made through open, spontaneous fermentation and relies upon the unique microorganisms from this region. Of course, spontaneous fermentation can take place anywhere with the proper conditions but lambic is unique to an area of Belgium through which the Zenne River passes.

To many craft beer lovers, the unique complexity and funky flavors of lambic offer an unparalleled drinking experience. And to properly shepherd this spontaneously fermented beverage from infancy to a delicious work of drinkable art requires tremendous skill. At the peak of this artful skill is the making of geuze. Geuze (pronounced with a hard ‘g’ and rhymes with ‘firs’) is made by blending one, two and three year old lambic that has aged in oak barrels or vats (known as foeders). Legendary beer writer Michael Jackson wrote that geuze “can have the toasty and Chardonnay-like notes found in Champagne”.

However, today’s popularity of lambic beers is relatively recent. In the 1970’s lambic style beers had spiraled towards beer obscurity and even teetered on the edge of obsolescence. During that timeframe, a young Frank Boon embraced brewing lambic beer. Over time his tireless efforts and leadership helped to revive the popularity of lambic beer as well as protect the traditional processes associated with making lambic. And today Frank Boon is an icon in the world of lambic brewing.

Making Lambic Beer

Frank Boon has said that “making lambic requires the following ingredients: water, lambic malt, wheat, aged hops, micro-organisms from the air of the Zenne valley, and a lot of patience.”

Malted barley and raw (unmalted) wheat are milled, transferred to a mash tun and then mixed with water. Lambic beers are made with 40% unmalted wheat and 60% lambic malt. The process involves labor-intensive mashing known as turbid mashing, allowing a lower water to grain ratio to be used while more effectively extracting carbohydrates from the grain. Turbid mashing creates cloudy wort that contains starches and proteins which have not been broken down by the enzymes in the mash into easily fermentable sugars. The cloudy wort is transferred to a boiling kettle and heated to near boiling temperatures resulting in a starch and protein rich liquid. The hot liquid is then added back to the main mash of grains, and the process is repeated several times.

The result of all that mixing and boiling is wort containing long-chain carbohydrates and sugars. While terrible for brewing most beers, the resulting long-chain molecules are the perfect food for microorganisms like Brettanomyces and lactobacillus to slowly digest over several years. And that’s extremely important since lambic beers are meant to develop through aging for long periods of time.

At the end, the grains are rinsed with extremely hot water (known as sparging). The wort collected from sparging is transferred to a boil kettle. Aged hops are added to the wort boil. Hops aged for a year or longer are used to introduce antibacterial compounds without imparting bitterness.

After boiling is complete, the wort is sent through a filter into an open-air, shallow vessel called a koelschip (coolship). Unlike most beers, lambic beers are made seasonally. Making lambic beer requires cooler nighttime temperatures. The cooler temperatures allow for spontaneous fermentation through exposure (inoculation) to airborne yeast and bacteria in the Zenne River Valley while minimizing harmful molds and bacteria. Hence, the brewing season lasts from about October to May, depending upon the weather as well as brewer discretion.

Next, the wort is transferred to wooden barrels or foeders where initial fermentation begins shortly thereafter. Typically lambic is aged in wood between one to three years. Each foeder can contain somewhat different yeast mutations and impart slight variations in the aroma and taste of the lambic. Frank Boon explained: “These foeders are very, very important for our brewery. The foeders are more than just a container. Through the foeders the yeast can pick up some oxygen. But not too much oxygen, otherwise the beer will oxidize. Each foeder imparts a different taste because the wild yeast that was picked up in the koelschip will remain active in the foeder and interact with previous generations of yeast still active in the foeder from the past. The old generations of Brettanomyces yeast strains have mutated and contribute to create a very special taste.”

Each foeder is tested regularly and when ready, the lambic can be bottled or kegged; moved to stainless steel tanks for combination with fruit; or blended to create geuze. Secondary fermentation is used in bottles and kegs to allow the beer to further develop over time. Karel Boon said: “Yeasts are transformers and they keep transforming in the bottle. Their actions not only contribute to the flavor and aroma, but they also absorb unwanted elements that settle to the bottom of the bottle. So to taste the beer without the sediment is what we have in mind. One great thing about lambic is that it ages and evolves in the bottle. Each of our bottles says you can age the beer for 20 years, although it can age even longer.”

My Quest to Learn About Brouwerij Boon

Having a personal love of lambic and geuze, I wanted to understand the story behind Frank Boon’s lambic brewing passion and journey. Fortunately, I had the good fortune to meet Frank Boon and son Karel at the Beer Bloggers and Writers Conference in 2017. As keynote speaker for the conference, Frank delivered a fascinating and detailed presentation about the history of lambic beer.

What struck me within 5 minutes of meeting Frank Boon was not only his dedication to producing quality lambic but also his passion for the cultural significance and history of this unique Belgian beer classic. And his sons, Jos and Karel, share that dedication and passion.

But the conference only provided me a prelude to the story I wanted to learn. I needed to learn more. So in September 2018 I traveled to Belgium and toured Boon brewery with Karel Boon to try to grasp the underlying nature of this passion, the journey to Frank Boon’s accomplishments and what the future holds for Brouwerij Boon. Here’s what I found out.

The Lure of Lambic and Geuze

As a child in the 1960s, Frank Boon developed an appreciation for complex aromas and tastes thanks to his mother who worked as a culinary journalist. As part of her job, Frank’s mother would try various food recipes and often modified them. She frequently cooked with beer or wine included in the recipe. Regularly she would ask Frank to try the recipe and seek his opinion. At the same time she would educate Frank about different flavors and flavor combinations. Frank’s educated palate would later be channeled in a very specific direction – lambic beer.

Frank also had a Grand Uncle that owned a brewery. Frank enjoyed going there and talking about beer with his uncle. There he learned about different beer styles and his interest in beer grew.

Karel Boon said: “My father got to know lambic beer when he was 16 years old. During the summer, he worked with friends on a farm picking apples. One day at the farm they had a wooden cask of lambic. It came from René De Vits in Lembeek.” (Lembeek is a city located in the municipality of Halle and the Zenne River Valley.) “And my father liked the beer. Later, he and his friends would buy beers from nearby small breweries. This included going to Mr. De Vits’ brewery to buy lambic and geuze. As a result, my father got to know René De Vits.”

At 18, Frank Boon moved from northern Brussels to Lembeek with his parents. The only person he knew in the area initially was René De Vits. With René De Vits as a mentor, Frank learned the basics of lambic brewing and blending. Frank said: “He made a fantastic bottle of geuze.” Frank also read numerous books to further his brewing education. Karel Boon explained, “My father did not have a formal education in brewing. He studied modern language and economics in secondary school (high school) until he was 18. My father then served in the army and later started officially as a blender at the age of 21. He is the example of a self-taught man.”

Shortly thereafter, René De Vits mentioned his plan to close the brewery. Frank expressed interest in acquiring the brewery, but there were two major problems:

- First, the 1970’s anchored the end of a massive decline in lambic brewers and geuze blenders. In fact, in 1970 only 11 breweries and 12 blenders existed as compared to 45 brewers and 120 blenders in 1945. This decline was partially due to lagers gaining popularity with younger Belgians and partially due to the inconsistent production quality among lambic brewers. Lambic and geuze were rapidly headed towards obscurity.

- Second, Frank did not have the funds or financial backing to acquire De Vits’ brewery even though De Vits was only seeking the cost of the buildings.

People thought Frank crazy. But where others saw the looming demise of lambic and geuze, Frank Boon saw opportunity and responsibility. He recognized the opportunity to fill a void in the sales of beer he loved and he embraced the responsibility to revive a Belgian cultural classic.

The Genesis and Evolution of Brouwerij Boon

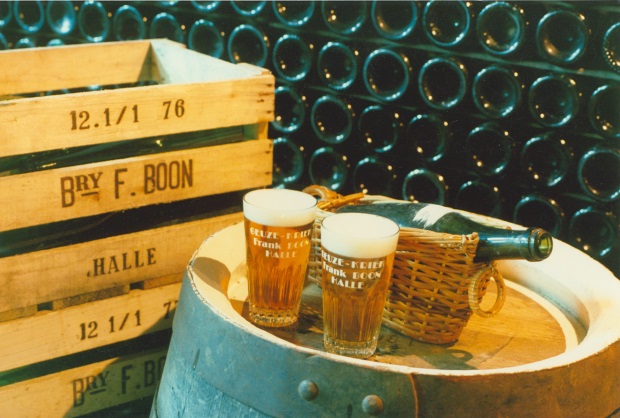

Frank Boon would not be deterred from his dream of creating lambic. Two months after turning 21 in 1975 (the legal age to start an independent business in Belgium at that time), Frank Boon started a cellar in Halle, Belgium where he blended lambic wort from Lindemans and Girardin. He also started a beer distribution business that promoted beer sales for small, local area Belgian breweries. The goal was to gain experience and enough funds through sales to support a bank loan to buy out René De Vits.

In 1978 Frank’s goal was realized. He bought the brewery/blendery from René De Vits in Lembeek and renamed it to Brouwerij Boon. From brewing to kegging to blending to bottling and sales, the work was labor intensive. Karel Boon said: “My father even had to make by hand the wire cages that held the cork on each bottle. They were not mass manufactured at the time.”

Business grew quickly and the original location for Brouwerij Boon worked for a time. However as business grew, Frank rapidly realized the existing site lacked adequate water, electricity, plumbing, and most importantly space. Lambic breweries are small companies but they need a lot of space – especially to store and age lambic stock in oak.

Looking to the future, Frank began to search for a new site to house the brewery. However, Frank also realized that it was impossible to develop the brewery further without a financial partner. And in 1985, Frank found a wine merchant partner who joined for a 50% stake in the brewery.

Having secured adequate funding, Frank bought an empty factory complex in Halle in 1986. The factory provided a lot of space – much more than initially needed – and provided room to grow. The site even had a building that Frank converted to his home and raised his family. This site is the current location of Brouwerij Boon.

With the increased space, Frank Boon switched from aging lambic entirely in barrels to primarily foeders. The brewery’s first foeder was Vat 79, which dates from 1883. This foeder is used exclusively to age 3 year old lambic. Said Karel Boon, “When you use and reuse a foeder for 3 year old lambic exclusively, the microorganisms in the foeder adapt themselves and mutate to convert the oak components in ways that contribute to the character and complexity of the beer. And each foeder has its own personality.”

By 1989, the wine merchant was no longer willing to invest in Brouwerij Boon. Lambic sales were down, but Frank moved forward. Over time, Frank Boon bought back all of the shares of the brewery. However, he realized that he would still need a partner to continue growth. Later on he found that partner in the Palm Brewery group and again sold a 50% stake in the brewery. The stake was transferred to Palm Brewing’s holding company at the time – Diepensteyn NV.

In the 1990’s, Frank spearheaded an effort to protect the origin, process, and character of traditional oak-aged lambic. Frank worked with other brewers in the area to establish protections for terms such as “Oude Lambic”, “Oude Geuze” and “Oude Kriek” by the European Union, resulting in assignment of Traditionally Specialty Guaranteed labeling in 1997. At the same time, Frank also worked with other breweries to establish the High Council for Traditional Lambic Beers (HORAL). HORAL is a consortium of lambic brewers and blenders that work together to promote lambic beers, brewing, and culture in Belgium.

In 2004, Frank recognized that much of his second hand equipment needed replacing. For example, his cast iron mash tun was from 1896. So he started planning for an on-site, modernized brewhouse. Frank’s plan incorporated design elements specifically geared to improve the quality, character and consistency of lambic production.

By 2010 the sales of Oude Geuze experienced a tenfold increase. Still using the old equipment, Frank Boon was struggling to keep up with the pace of sales. And by the end of 2012, Brouwerij Boon was selling more beer than they could brew.

Fortunately, the new brewhouse had started construction in 2011 and completed in 2013. In March 2013, the first lambic was brewed in the new brewhouse, the same month as the last lambic in the old brewhouse. And with its modern brewhouse, Brouwerij Boon created and built up lambic stock at a pace to stay ahead of market demands.

Today Brouwerij Boon is the largest producer of traditional lambic beer. With over 150 foeders, Brouwerij Boon has more lambic stock aging in oak than anyone else in the world. Approximately 70 to 75% of Boon’s beers are sold regionally in Belgium.

A Vision to the Future

Frank Boon is still the driving force behind Brouwerij Boon, but the long-term future will rest upon sons Jos and Karel. Jos and Karel grew up at the brewery. And both are dedicated to preserving Frank’s vision as well as the tradition, character and quality of Boon lambic beers. Jos works in Boon’s brewery operations and has formal education from the University of Leuven in the field of bioengineering with a specialty in malting and brewing. Karel works in Boon’s business operations as head of marketing, sales and logistics. He also interned for six months at Chimay Brewery.

Karel Boon said:

“The brewery is part of who we are. It’s part of our lives. We grew up at the brewery. When we were kids, the brewery and the surrounding empty buildings were our playground. We rode around on our bikes. The brewery was smaller then so we had empty rooms in which we could play. And we also had daily chores at the brewery.”

“Our father never pushed us. When he would go on trips to other breweries or other beer-related events, he would ask us if we’d like to go also. Frequently we went with him so we had lots of beer industry exposure. However, Jos and I have a brother and sister that chose different career paths.”

“Jos made it very clear early-on that he wanted to work at the brewery as his career. Even at 10 years old, he would come home from school, put his backpack away and then head straight to the brewery to watch operations. I have a photo of him at age 8 driving a forklift carrying spent grains to put on a farmer’s truck. He’s always been very active at the brewery.”

“I had an interest too but also had other areas of interest – piano, computers, and information technology. At some point I needed to make a choice about my career path. I finally decided that the brewery was where I wanted to be also but in the marketing, sales and logistics areas.”

“My father started with nothing and built this business. He looked at the business differently. It’s important to keep going and growing as a family business.”

As I toured the brewery with Karel Boon, there were obvious signs and sounds of ongoing construction. Once again the brewery was undergoing renovation and modernization. Karel explained that as a lambic producer you must always look to the future. These were words I had heard before from Frank Boon.

The construction made me wonder and ask about Boon’s philosophy with respect to merging tradition with modernization in lambic production. Karel Boon explained: “You must start by focusing on quality – getting the flavors and consistency right. Some people have a romantic view of a brewery with dust and cobwebs and old technology. But working with outdated technology is counterproductive to that goal of quality. Technology transitions have always brought controversy. Even in the 1800s there was controversy when lambic producers switched from wooden mash tuns to cast iron tuns and copper pipes. But it’s not about technology, it’s about process. So we follow the same traditional methods, the same steps regardless of the technology used. And we use modern equipment to improve efficiency and to help us refine the quality and character of the final product without compromising the traditional process. We never compromise on product quality. And we stick to regional tradition and product authenticity.”

November 2018 marked 43 years since Frank Boon started his journey as a lambic blender and brewer. Frank, Jos and Karel celebrated by sweeping the Gold, Silver and Bronze medals in the Brussels Beer Challenge for the specialty beer category of Old Style Gueuze-Lambic.

From what I’ve seen and heard, the future of Frank’s legacy is in good hands. And after all, a lambic producer must always look to the future.